These ‘fables’ – and here I’m taking ‘any tale in a literary form, not necessarily probable in its incidents, intended to instruct or amuse’ as a definition – written between 2006-2014, began as occasional pieces linked through their singular method of composition. Sometimes they resemble (or I like to think they resemble) curious little stories penned in the 1930s by a central European with a surrealist bent, as translated by an earnest Englishman who doesn’t really understand the joke; at other times they are more careworn, their humour abraded by the circumstance of their settings. A number of them feature characters cast adrift from benighted times, taking refuge in whimsical invention; most too are lightheartedly serious.

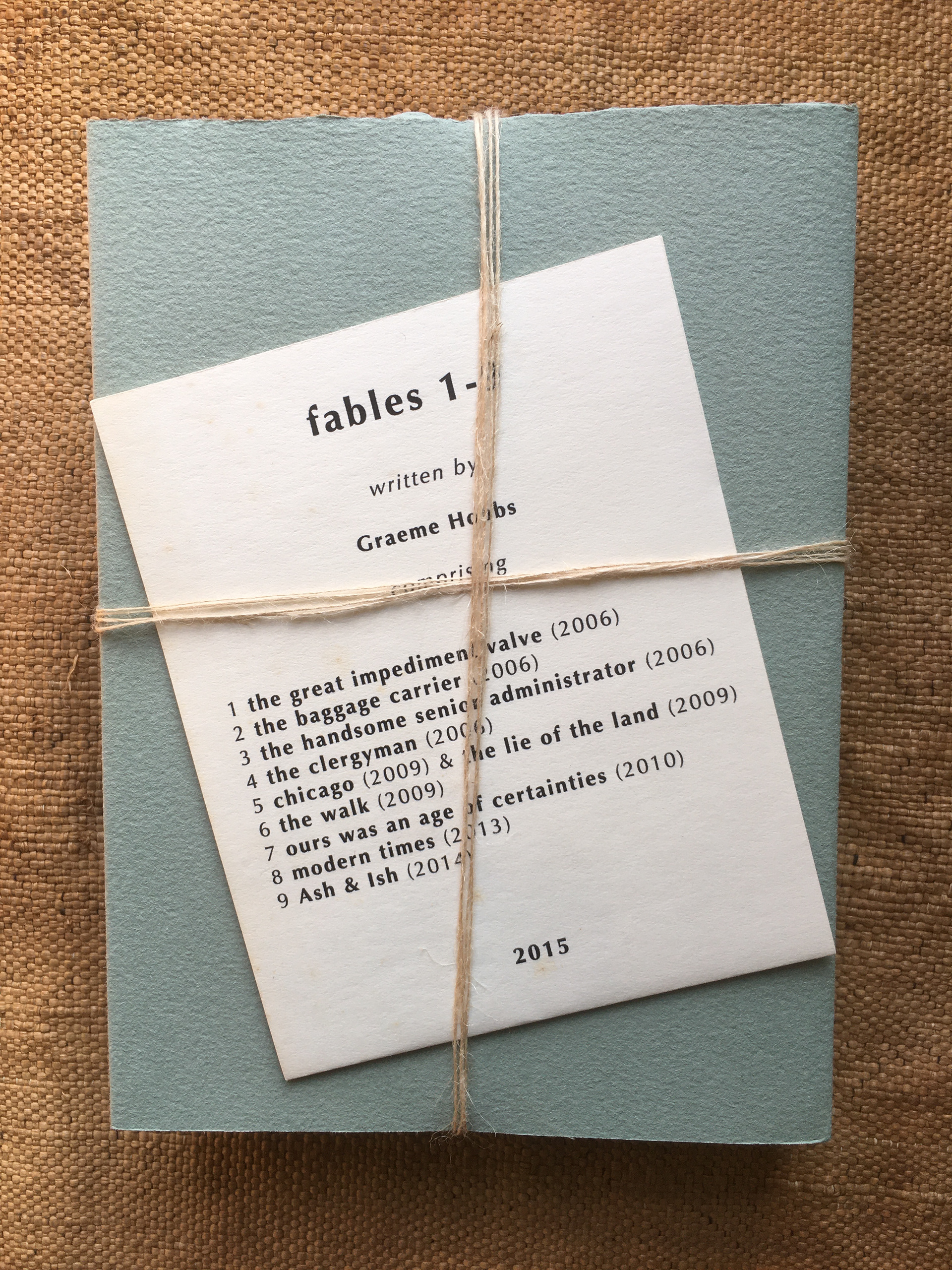

My usual ambivalence to titles is plain (so much undue meaning freighted on to a word or phrase) as the titles don’t actually appear on the cover, which instead spreads the load between the series, an image – taken, as all the rest in the run, from Wills’s 1923 set of Gardening Hints – and the first line of the tale. The pea green wrappers are Ruscombe Mill’s Forest Green Wove 180gsm paper.

9 Ash & Ish (2014) First the full stops went, then the commas, then the apostrophes, then all other punctuation, until nothing was left but the bare comic tale of Ash, who one day just stops in the street. As passers-by turn him into a fetish figure, draping him with the adornments of their predilections, and the authorities decide what to do with him, worrying that he constitutes a fire hazard, Ish, Ash’s inside other, is left harried and frantic, rushing around trying to kick-start his engine, but to no avail. A pretty pass, all told.

8 Modern Times (2013)

Where is this one set? A down-at-heel encampment for low-key dissidents perhaps, engaged upon their work of tidying up anomalies in official pronouncements, where jocular camarderie is not quite enough to still the slivers of threat that poke through the cracks: ‘bring me the silver of your stream, says the knife grinder, bring me its golden light.’ It ends (as a number of my stories seem to these days) with thistledown upon the air.

Where is this one set? A down-at-heel encampment for low-key dissidents perhaps, engaged upon their work of tidying up anomalies in official pronouncements, where jocular camarderie is not quite enough to still the slivers of threat that poke through the cracks: ‘bring me the silver of your stream, says the knife grinder, bring me its golden light.’ It ends (as a number of my stories seem to these days) with thistledown upon the air.

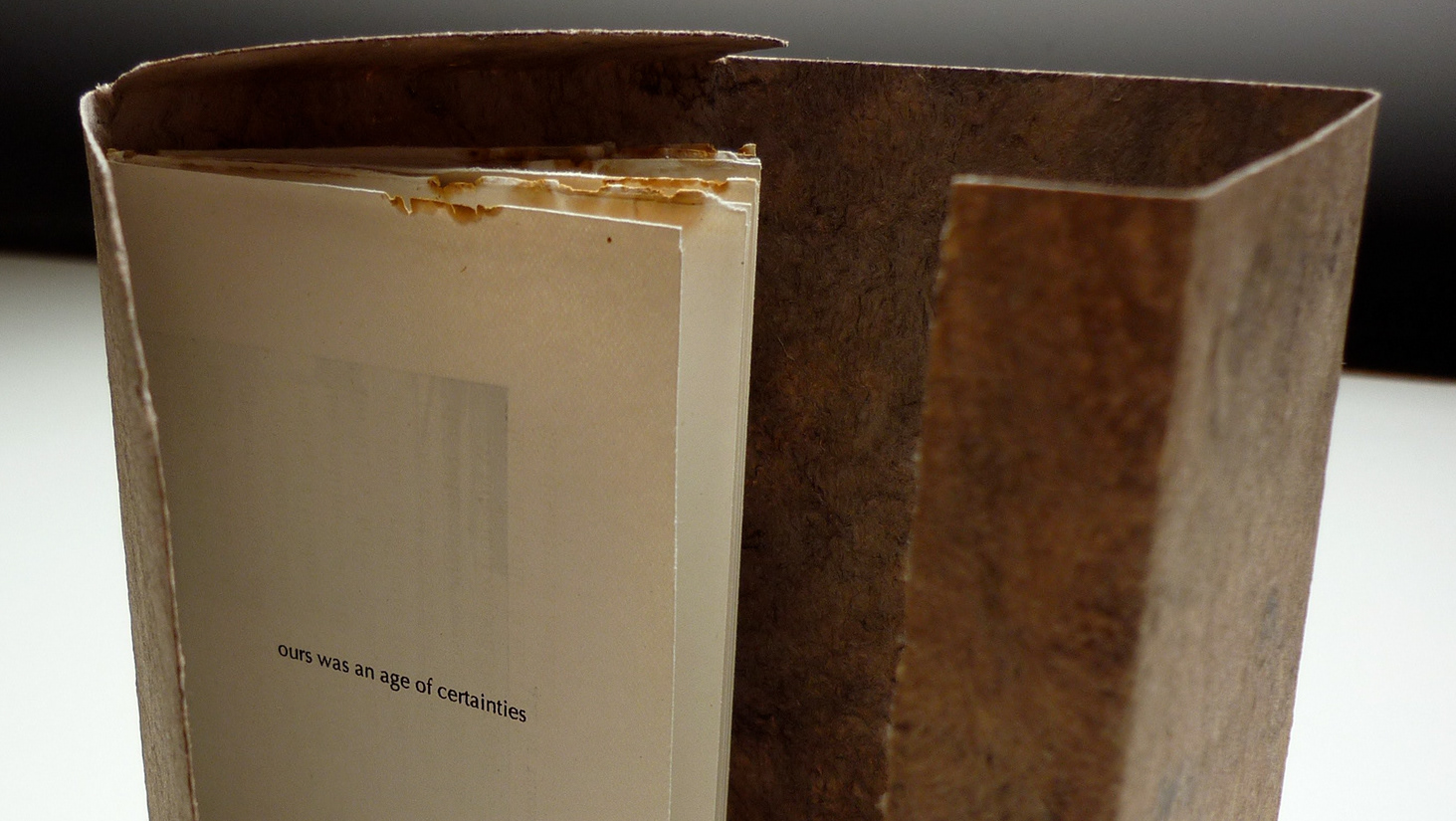

7 Ours was an Age of Certainties (2010) An anonymous, broken narrative from a displaced time (or vice versa). Originally made in 2012 as a small book wrapped in tree-bark paper.

6 The Walk (2009) A walk of sorts, engaged upon by a man of less than moderate means and fewer prospects, that commences with the promise of springtime hemlines and ends in the middle of his outing, between his destination and his desk. And I rather like the ‘Gardening Hints’ card I used for the cover, on two ways of staking runner beans. Thus far, I have always gone for the more traditional method of ‘A’, but can see the benefits of ‘B’ – a sort of hop twine arrangement to which I shall give serious consideration next year.

5 Chicago & The Lie of the Land (2009)

The remainder of the stories – 4 The Clergyman (2006), 3 The Handsome Senior Administrator (2006), 2 The Baggage Carrier (2006) and 1 The Great Impediment Valve (2006), originally formed the contents of the booklet, The Great Impediment Valve (2006). The basis of the stories was the lists of homophones, homonyms and word definitions extracted from four source texts, to which these stories otherwise bear no relation. The only ‘rule’ was that the extracted words needed to be used in the same order for the new stories, which took me, and the characters, in directions they wouldn’t otherwise have taken. Which was precisely the point. In this regard, it’s worth quoting Harry Mathews from his foreword to Immeasurable Distances, in which he says: ‘The written word, like the languages of the other arts, constitutes a predetermined, autonomous system. The primacy of subject matter, or ‘depth’, is a distracting cultural illusion – there exists only surface and a reader bringing awareness to bear on it. In terms of the age-old poetic tradition of truth-telling, writing the truth means not representation but invention.’